Our Story

We are descendants of the royal families of Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski and the Yerevan nobility. After the Russian Revolution, our ancestors spread across the world, settling in various countries, including the United States. They left behind stories, testimonies, and memories. We hope to keep our family’s history alive by sharing them here.

Fearing repression after the revolution, many of our forefathers changed their names and chose to live a quiet existence away from the spotlight. We have tried to reach out to other relatives, many of whom remain afraid to speak about the past.

We’ve heard countless stories of massacres and killings, so we understand why some family members prefer not to revisit our traumatic history.

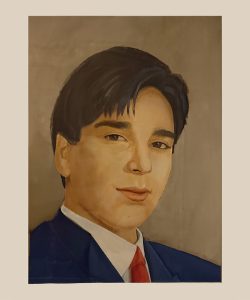

Prince Cyrus Khan Kangarli Nakhchivansky

The official biographer and current head of the Nakhchivanski family, Prince Cyrus Khan is the Great Grandson of Prince Bahram Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski.

The ancestry of Prince Cyrus Khan could be traced back to several of the most significant ruling dynasties from the South Caucasus and Northwestern Iran. Seven reigning dynasties and ruling houses are united through his descent, namely the Kangarli, Nakhchivanski, Javanshir, and Karabakh Khanates, but also bearing connections to the Qajar Dynasty and the Makinsky family of the Maku Khanate.

This fascinating convergence of diverse lineages of historical importance in Cyrus Khan’s heritage puts him in a unique position as not only the custodian and archivist of his family’s rich and storied past, but also inspired a profound sense of responsibility to dedicate his life to preserving their true legacies.

Read more about Prince Cyrus here.

Prince Bahram Khan Kangarli Nakchivanski

Our Great Grandfather, Prince Bahram Khan Kangarli Nakchivanski, was the last ruler and last General Governor of Nakchivan in 1919.

Prince Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhchvanski

Our family were predominantly Russian speaking. One of our ancestors was Prince Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhchvanski.

Prince Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski, or Nakhichevansky, francised spelling: Hussein Nahitchevansky (Azerbaijani: Hüseyn xan Naxçıvanski; Russian: Гусейн-хан Нахичеванский or Хан-Гуссейн Нахичеванский) (28 July 1863 in Nakhchivan City – January 1919 in St. Petersburg), was a Russian Cavalry General of Azerbaijani origin. He was the only Muslim to serve as General-Adjutant of the H. I. M. Retinue.

Born: 28 July 1863, Nakhchivan City, Erivan Governorate

Died: January 1919 (aged 55) St. Petersburg

Allegiance: Russia Russian Empire

Service/branch: Cavalry

Years of service: 1883-1919

Rank: General of the Cavalry, General-Adjutant

Commands held: Life-Guards Horse Regiment, 2nd cavalry corps, Guard Cavalry Corps

Battles/wars: Russo-Japanese War, World War I

Awards: Order of St. George of 4th degree, Order of St. George of 3rd

He was born on July 28, 1863 in Nakhchivan City (now the capital of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in Azerbaijan). His paternal grandfather Ehsan Khan Nakhchivanski was the last ruler of the Nakhchivan Khanate. Huseyn Nakhchivanski’s parents were Kalbali Khan Nakhchivanski, a major-general in the Russian Army, and Khurshid Qajar-Iravani, a member of a branch of the Qajar dynasty who ruled the Erivan khanate (abolished in 1828).

In 1874, Huseyn Nakhchivanski was admitted to the Page Corps and graduated with honours in 1883. He received the rank of cornet and was assigned to the elite Leib Guard Horse Regiment. Nakhchivanski served there for twenty years and ascended positions from cornet to Colonel of the Leib Guard.

When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, Huseyn Khan was seconded to Petrovsk-Port to form from volunteers the 2nd Dagestani cavalry regiment. During the war the regiment distinguished itself, and Khan Nakhchivanski himself received seven decorations. On January 27, 1907 he was decorated with a fourth-degree Order of Saint George for launching a successful cavalry onslaught to save an encircled Russian infantry unit. He was also awarded the golden Saint George sword.

Khan Nakhchivanski was the commander of 44th Nizhegorodski Dragoon regiment from November 1905, and in 1906, he was made Fliegel-Adjutant of H. I. M. Retinue and appointed the commander of Leib Guard Horse Regiment, where he started his military career. In 1907, he received the rank of major-general. In 1912, he was appointed the commander of 1st detached cavalry brigade, in 1914 he was conferred the rank of lieutenant-general and made the commander of 2nd Cavalry Division and in this position entered World War I. In August 1914, Khan Nakhchivanski was the head of the cavalry group on the right flank of 1st army. From October 19, 1914 he was commander of the 2nd cavalry corps and on October 22, 1914, he was decorated with the Order of Saint George of III degree, which was presented to him personally by Tsar Nikolas II. In June 1915, he was appointed General-Adjutant of His Imperial Majesty and became the only Muslim to hold that position. On November 25, 1915, Huseyn Khan was seconded to the chief commander of the Caucasian Army and on January 23, 1916 he was promoted to the rank of the General of the Cavalry. He was the commander of Guard Cavalry Corps from April 9, 1916 and took part in Brusilov Offensive.

Emigration to Lebanon

After the October Revolution (1917), Prince Huseyn Khan’s wife, Sophia Taube (daughter of Russian poet Nikolai Gerbel), and their children emigrated from Russia. Their descendants settled in several countries, including Lebanon.

Sophia passed away in Beirut in 1941; descendants—Tatiana included—settled in Lebanon, France, Egypt, the US, and Canada

The Russian Revolution

When in the winter of 1917 the February Revolution began in Petrograd (present-day Saint Petersburg), Nakhchivanski was one of the two Russian generals (alongside Fyodor Arturovich Keller) who supported the Czar and sent a telegram to the headquarters of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief to offer Nicholas II the use of his corps for suppression of the revolt, but Nicholas II never received this telegram.

After the abdication of Nicholas II, Khan Nakhchivanski refused to serve the Russian Provisional Government. He was dismissed from the army and lived with his family in Petrograd. He was one of the few Azeri figures who didn’t support the newly formed Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, remaining a staunch Russian monarchist. After the October revolution and the assassination of the head of Petrograd Cheka, Moisei Uritsky, Nakhchivanski together with some other prominent citizens of Petrograd was taken hostage by the Bolsheviks. He was kept in the same prison with Grand Dukes Paul Alexandrovich, Nicholas Mikhailovich, George Mikhailovich and Dmitry Konstantinovich. Also in the same prison was kept Prince Gabriel Constantinovich, who used to serve under the command of Khan Nakhchivanski and who later managed to escape, and who mentioned in his memoir that he met Khan Nakhchivanski during the walks in the prison yard.

The Grand Dukes were executed in the Peter and Paul Fortress in January 1919. It is presumed by a number of historians that Khan Nakhchivanski was executed together with the Grand Dukes. However the exact circumstances of Khan Nakhchivanski’s death and his burial place still remain unknown.

Ca. 1890, Nakhchivanski married Sophia Taube (née Gerbel; 1864, St. Petersburg – 1941, Beirut), daughter of the Russian poet and translator Nikolai Gerbel. Together they had three children: Nicholas (died in 1912), Tatiana and Georges. After the October Revolution, the Nakhchivanskis emigrated. Their descendants lived (and some continue to live) in France, Lebanon, Egypt, and the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Iran.

who was our great great uncle. His family had a kingdom between Iran and Russia. He become a soldier of russian army and he was nominated to be a Russian prince. He was a general, he has prozes and honors. He is known in history as a person who the tsar Nicolas II was trusted and counted on during the revolution.

Prince Jafargulu Khan Kangarli Nakchivanski

Prince Jafargulu Khan Kangarli Nakchivanski in December 1918 declared the republic of Arks who led to The republic of Azerbeijan and was founded by our family. The Arras later became azarbaijan.

Prince Jafargulu Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski

Connected to: Azerbaijan Major General Shusha

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Prince Jafargulu Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski (Azerbaijani: Cəfərqulu xan Naxçıvanski, Russian: Джафаркули-хан Нахичеванский; 5 February 1859, Nakhchivan – 1929, Shusha) was a Russian Imperial officer and later an Azerbaijani statesman. He was the brother of General-Adjutant Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski and father of Major General Jamshid Nakhchivanski.

Early life and military career

Prince Jafargulu Khan was born into a princely family of Nakhchivanski, descending from the rulers of the Nakhchivan Khanate. His father was a Major General of the Russian Imperial army and his mother was the daughter of the khan of Maku. In 1867, young Jafargulu was signed up for the Page Corps. Upon graduating in 1877, he was promoted to cornet in Her Majesty’s Uhlan Life Guard Regiment based in Peterhof. In April 1878, he was sent to a regiment stationed in the Caucasus and participated in the Russian occupation of Erzurum during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). In the later years, he participated in Central Asian campaigns of the Russian army, after which he was promoted to Staff captain. For his participation in these military operations, he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislaus (third degree, 1880), Order of Saint Vladimir (fourth degree, 1881) and Order of Saint Anne (third degree, 1882), as well as medals in commemoration of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and for the siege of Geok Tepe.

In 1885 he was elevated to captain of cavalry and retired. In 1903, he was appointed mayor of Nakhchivan. From 1912 to 1917, he was honorary magistrate of Erivan.

Political activity

Following the disintegration of the Russian Empire, Azerbaijan and Armenia, now both independent, quarrelled over the region of Nakhchivan. When in December 1918 it became clear that the British Chief Commissioner Sir John Oliver Wardrop’s peace plan would assign Nakhchivan to Armenia instead of Azerbaijan, Nakhchivanski initiated an Azeri revolt, leading to the proclamation of the independence of the Republic of Aras.

Named after the Aras river, the Republic of Aras was a short-lived state established in December 1918 as a direct response to the intense territorial disputes between Armenia and Azerbaijan following the

collapse of the Russian Empire following World War I. by Prince Jafargulu Khan Nakhchivanski, composed of the former uyezds of Nakhchivan, Sharur-Daralagez and Surmali, with its capital in the city of Nakhchivan. Nakhchivanski became the head of the new republic, which in essence was de facto controlled by Azerbaijan. In May 1919, in the midst of the Armenian–Azerbaijani War, Armenia advanced its troops into it and managed to capture the city of Nakhchivan by June 1919. There it clashed with regular Azerbaijani troops, which reinstalled Azerbaijan’s control over the city within a month. On 10 August 1919, the Armenians were forced to sign a peace treaty.

In summer 1920, in the aftermath of the Soviet annexation of Azerbaijan, the Armenians of Nakhchivan revolted. The Soviet Army entered Nakhchivan and quickly suppressed another the revolt. Jafargulu Khan Nakhchivanski was arrested by the Bolsheviks allegedly for “spreading anti-Soviet propaganda”. He was incarcerated in Baku and claimed innocence in the petitions he sent to the Temporary Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan. His appeal was discarded; he was found guilty and transferred to a prison in Shusha, where he died in 1929.

Prince Jamshid Jafargulu oglu Nakhchivanski

Prince Jamshid Jafargulu oglu Nakhchivanski (Azerbaijani: Cəmşid Cəfərqulu oğlu Naxçıvanski; August 23, 1895 – August 26, 1938), also known as Jamshid Khan Nakhichevanski, was a Russian Imperial, Azerbaijani and Soviet military commander. He rose to the rank of Combrig (equivalent to Brigadier General) in the Soviet Army.

rank: Combrig

Battles/wars: Armenian–Azerbaijani War, Battle of Baku, World War I

Awards Order of the Red Banner of Labour, Order of Saint Stanislaus (2nd and 3rd degrees), Order of St. Anna, Cross of St. George (4th degree)

Prince Jamshid Nakhchivanski was born to the family of retired Russian Imperial Rittmeister Jafargulu Khan Nakhchivanski who was the brother of General Adjutant Huseyn Khan Nakhchivanski. The Nakhchivanskis came from roots of Kangarli Oghuz Turks tribes descendants of which ruled the Nakhchivan Khanate. At the age of seven, his mother Farrantaj-hanim taught him to write in Azerbaijani and his nanny taught him Russian and French. In 1904, he was admitted to Tiflis Cadet Corps graduating in 1911.

Imperial Russian Army

On August 30, 1914 he started his service as junker of Yelizavetgrad Cavalry School. Having graduated from the four-month 1st-grade intensive course, he was appointed praporshchik and assigned to Azerbaijani reserve cavalry regiment of the Caucasian Native Mounted Division which was formed from Muslim volunteers from Caucasus and Transcaucasus. On June 14, 1915, Jamshid Khan was transferred to the regiment and on August 22 he was promoted to the rank of Cornet. On February 14, 1916, he was awarded his first military award of Order of Saint Anna of 4th degree. On 26 January 1917 Jamshid Khan was decorated with St. George sword for defeating the enemy and leading a cavalry attack, despite being wounded twice. In March 1917, Jamshid Khan was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislaus of 2nd degree for his bravery on Romanian front. On April 15 he was awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 3rd degree and on August 22 with Cross of St. George of 4th degree.

On October 30, 1917, Nakhchivanski was conferred the rank of stabs-rittmeister, and his regiment was made a part of the Russian Caucasus Army and relocated to the Caucasus. At the end of 1917, at Special Transcaucasian Committee orders, the formation of Muslim (Azerbaijani) Corps under Lieutenant General Ali-Agha Shikhlinski’s command began.

Azerbaijani Army (ADR)

By end of May 1918, the establishment of the corps was completed. After the declaration of independence of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic on June 26, 1918, the corpus was transferred to Azerbaijani Army corps. In July 1918, the corps dissolved and were partially integrated with newly arrived Turkish 5th Caucasian and 15th Chanahkala divisions and newly formed Caucasian army of Islam led by Nuru Pasha. During the battles in the outskirts of Goychay on June 27 – July 1, 1918, the Army of Islam destroyed the 1st Caucasian corps of the Red Army. Jamshid Khan took part in the Battle of Baku against the Centrocaspian Dictatorship and Armenian Dashnaks. Baku was liberated on September 15, 1918.

In the Azerbaijani Army, Jamshid Khan was the commander of the 1st company of 1st Azerbaijani regiment and assistant to regiment commander. On March 24, 1920 Minister of Defense of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic Samad bey Mehmandarov appointed Lieutenant Colonel Jamshid Khan Commander of 2nd Karabakh cavalry regiment. While in Karabakh he participated in liberation of Shusha.

Soviet Army

After the establishment of Soviet rule in Azerbaijan, the Karabakh division was transferred under command of the Red Army. Following the suppression of the 1920 Ganja revolt, Bolsheviks arrested many Azerbaijani officers including Nakhchivanski. He was kept in prison on Nargin island in Baku Bay but was released in two months to serve in the administration of Red Commanders School. He then served as Commander of the Azerbaijani Rifle Division from 1921 to 1931.

On February 22, 1931 he was called to Red Army corps in Tbilisi where he was arrested and accused of treason and anti-Soviet espionage. On September 30, 1931 he was sentenced to death but Sergo Ordzhonikidze prevented the execution by taking the issue to Politburo where Joseph Stalin ordered to release Nakhchivanski provided that he wouldn’t work and live in Caucasus. Nakhchivanski was rehabilitated in the army and sent to Frunze Military Academy for further studies. In 1933, he completed his studies and stayed at the academy to teach military tactics. On December 5, 1935 by the order of People’s Commissar of Defense Kliment Voroshilov he was conferred the rank of Combrig.

Death

During the Great Purge, Nakhchivanski was arrested on May 20, 1938 and was charged with anti-Soviet activities and espionage on August 26, 1938 in Lefortovo prison. He was sentenced to death and confiscation of all personal property. Nakhchivanski was executed by firing squad. His body was transported and buried in Kommunarka shooting ground, an NKVD burial site for repression victims, 26 km outside of Moscow. On December 22, 1956 he was rehabilitated.

In 2007, 112th anniversary of Jamshid Nakhchivanski was celebrated in Azerbaijan streets in Baku and Nakhchivan as well as Jamshid Nakhchivanski Military Lyceum were named after Jamshid Khan Nakhchivanski. A house museum in Nakhchivan was also opened by Azerbaijani government.

Combrig

Battles/wars: Armenian–Azerbaijani War, Battle of Baku, World War I

Awards: Order of the Red Banner of Labour, Order of Saint Stanislaus (2nd and 3rd degrees), Order of St. Anna, Cross of St. George (4th degree)

Prince Kalbali Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski

Prince Kalbali Khan Kangarli Nakchivanski was given to Petersburg aristocratic school at the age of 14 but had to return to Nakhchevan suddenly for illness. After treatment in 1849 he voluntarily participated in Dagestan march, and was awarded the rank of an officer for the bravery shown in the battles. He fought with courage in the Crimean War (1853-1856), was appointed as commander of lifeguards to Gusar regiment in 1855. Being appointed as commander of Iravan cavalry brigade, consisting of Azerbaijanis at the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-78 Nakhchivanski showed great courage in military operations.

Prince Ehsan Khan Kangarli Nakhichevansky

Prince Ehsan Khan Kengerli (Azerbaijani: إحسان خان کنگرلی), later known by his Russified name of Ehsan Khan Kangarli Nakhichevansky (Russian: Эхсан Хан Нахичеванский, Azerbaijani: إحسان خان ناخچیوانسکی; 1789–1846) was the last ruler of the Nakhichevan Khanate.

Ehsan Khan hailed from the Turkic tribe of Kengerli, and was the youngest son of Kelbali Khan, the ruler of the Nakhichevan Khanate, who was blinded by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar.

In his youth, Ehsan Khan was on Persian service and later took part in Ottoman–Persian War (1821–23). During the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828, Abbas Mirza appointed Ehsan Khan as commander of the fortress Abbasabad. After the Russians laid siege to the fortress, Ehsan Khan secretly arranged for the gates of the fortress to be opened to the Russian commander General Ivan Paskevich.

For his services, Ehsan was conferred the rank of colonel and appointed the ruler of the Nakhichevan Khanate. The khanate was formally abolished in 1828, but Ehsan Khan retained his influence in the region and was appointed the campaign ataman of Transcaucasian Muslim troops. In 1831 he was decorated with 2nd class Order of Saint Anna, and in 1837 he was conferred the rank of major-general in the Russian army.

After the dissolution of the khanate, the khans of Nakhichevan took the Russified surname Nakhchivanski, and the men of its family traditionally joined the Russian military service. Two sons of Ehsan khan – Ismail khan and Kalbali khan – were generals in the Russian army and were awarded orders of Saint-George IV degree for their actions in battle. A son of Kalbali khan, Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhichevanski, was a prominent Russian military commander and adjutant general of the Russian Emperor, and his nephews, Jamshid Khan and Kalbali, were generals in the Soviet and Iranian armies respectively. His great great grandson Jafargulu Khan Nakhchivanski initiated an Azeri revolt, leading to the proclamation of the independence of the Republic of Aras, composed of the former uyezds of Nakhchivan, Sharur-Daralagez and Surmali, with its capital in the city of Nakhchivan.

Feyzullah Mirza Qajar

Feyzullah Mirza Qajar (Russian: Фейзулла Мирза Каджар; Persian: فیض الله میرزا قاجار; Azerbaijani: Feyzulla Mirzə Qacar) also Fazullah-Mirza Qajar (Russian: Фазулла-Мирза-Каджар; Persian: فضل الله میرزا قاجار) (b. December 15, 1872 – d. 1920) – was a prince of Persia’s Qajar dynasty and a decorated Imperial Russian and Azerbaijani military commander, having the rank of Major-General. In the Russian imperial army, he was the commander of the 1st Caucasian Native Cavalry Division, and the commander of Ganja garrison in the army of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

Born: 15 December 1872, Shusha, Elisabethpol Governorate, Russian Empire

Died: 1920 (aged 47–48), Boyuk Zira, Baku

Allegiance: Russia Russian Empire, Azerbaijan ADR

Service/branch: Cavalry

Years of service: 1891—1920

Rank: Major General

Commands held: Chechen cavalry regiment, The 2nd Brigade of the Caucasian Native Cavalry Division, 1st Savage Division, Army Cavalry Division of the ADR

Battles/wars: Russo-Japanese War, First World War

Awards: Order of St. George, Order of Saint Anna

Early life

He was born on 15 December 1872 to Shafi Khan Qajar in Shusha, Elisabethpol Governorate. He was a senior great-grandson of Bahman Mirza. He received general education in the Tbilisi Cadet Corps. Starting the military the service on 30 August 1891, he started his second education at the Nikolayev Cavalry School. After graduating from college in the 1st category, he was released on August 7, 1893 as a cornet to the 43rd Tver Dragoon Regiment. He was promoted to lieutenant rank on 15 March 1899. On November 20, 1901, he was appointed acting head of the regiment’s weapons and non-combat team. March 15, 1903 promoted to headquarters captain.

Feyzullah Qajar among the Savage Division, c. 1917t

Not to be confused with Soviet–Japanese War.

The Russo-Japanese War ( Japanese: 日露戦争, romanized: Nichiro sensō, lit. ’Japanese-Russian War’;Russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, romanized: Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1905 over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major theatres of military operations were located in Liaodong Peninsula and Mukden in Southern Manchuria, and the seas around Korea, Japan, and the Yellow Sea.

Russo-Japanese War

Clockwise from top: Russian cruiser Pallada under fire at Port Arthur, Russian cavalry at Mukden, Russian cruiser Varyag and gunboat Korietz at Chemulpo Bay, Japanese dead at Port Arthur, Japanese infantry crossing the Yalu River

Russia sought a warm-water port on the Pacific Ocean both for its navy and for maritime trade. Vladivostok remained ice-free and operational only during the summer; Port Arthur, a naval base in Liaodong Province leased to Russia by the Qing dynasty of China from 1897, was operational year round. Since the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan had feared Russian encroachment would interfere with its plans to establish a sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria. Russia had pursued an expansionist policy east of the Urals, in Siberia and the Far East, since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century.

Seeing Russia as a rival, Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of Korea as within the Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused and demanded the establishment of a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan in Korea north of the 39th parallel. The Imperial Japanese Government perceived this as obstructing their plans for expansion into mainland Asia and chose to go to war. After negotiations broke down in 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy opened hostilities in a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur, China on 9 February 1904.

Although Russia suffered a number of defeats, Emperor Nicholas II remained convinced that Russia could still win if it fought on; he chose to remain engaged in the war and await the outcomes of key naval battles. As hope of victory dissipated, he continued the war to preserve the dignity of Russia by averting a “humiliating peace”. Russia ignored Japan’s willingness early on to agree to an armistice and rejected the idea of bringing the dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. The war was eventually concluded with the Treaty of Portsmouth (5 September 1905), mediated by US President Theodore Roosevelt. The complete victory of the Japanese military surprised international observers and transformed the balance of power in both East Asia and Eastern Europe, resulting in Japan’s emergence as a great power and a decline in the Russian Empire’s prestige and influence in eastern Europe. Russia’s incurrence of substantial casualties and losses for a cause that resulted in humiliating defeat contributed to a growing domestic unrest which culminated in the 1905 Russian Revolution, and severely damaged the prestige of the Russian autocracy. The war also marked the first victory of an Asian country against a Western power in modern times.

Awards

- Order of St. Anne 4th rank with the inscription “for courage” (3 November 1904)

- Order of St. Stanislav 3rd rank with sword and ribbon (9 January 1905)

- Order of St. Anne 3rd rank with sword and ribbon

- “For the successes in struggles with the Japanese” (25 June 1905)

- Order of Lion and the Sun 3rd degree (28 January 1907)

- Order of St. Stanislav 2nd rank with sword (31 January 1915)

- Order of Saint Vladimir 4th rank with sword and ribbon (14 March 1915)

- Order of Saint Vladimir 3rd rank with sword (15 July 1915)

- Order of St. Anne 2nd rank with sword (9 September 1915)

- Order of St. George 4th rank with sword (17 October 1915)

Family

He was married to Khurshid Nakhchivanskaya (1894-1963) a singer in Azerbaijan State Opera and Ballet Theatre, daughter of Rahim khan Nakhchivanski, elder brother of Jamshid Nakhchivanski.

Prince Ismail Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski

Prince Ismail Khan Ehsan Khan oghlu Nakhchivanski (Azerbaijani: İsmayıl xan Ehsan xan oğlu Naxçıvanski; 5 January 1819 – 10 February 1909) was a Azerbaijani Cavalry General in Imperial Russian Army. He was the son of Ehsan Khan Kangarli Nakhichevansky and uncle of Huseyn Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski. His brother Kelbali Khan Kangarli Nakhchivanski was also Cavalry General in the Russian Imperial Army.

Born:5 January 1819, Nakhchivan Khanate

Died: February 1909 (aged 90), Nakhchivan City, Erivan Governorate

Allegiance: Russia Russian Empire

Service/branch: Cavalry

Years of service: 1839-1908

Rank: General of the Cavalry

Commands held: “Kengerly Cavalry”, “Erivan Bey Regiment”, “Erivan Cavalry Irregular Regiment”

Battles/wars: Crimean War, Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

Prince Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski was born on 5 January 1819 in the family of the ruler of Nakhichevan, Ehsan Khan (1789–1846). He received his primary education at the Tiflis Noble Gymnasium. From a young age, under the commandment of his father, he served in the “Kengerly Cavalry”. In 1837, the “Kengerly Cavalry”, as an honorary convoy, accompanied the Emperor Nicholas I, who arrived to the Caucasus. The honorary convoy also included the 18-year-old Ismail Khan. Among other escorts, he was awarded by the emperor a silver medal on the ribbon of the St. Vladimir Order. Ismail Khan began his service in the Russian Imperial Army on 1 May 1839 in Warsaw in the Transcaucasian Muslim Horse Regiment naibom (as assistant commander of a Sotnia). “For distinction in service” during the inspections and manoeuvres near Warsaw in 1840, he was promoted to Praporshchik on 28 October 1840. On 27 December 1841, Ismail Khan was promoted to lieutenant, and on 3 March 1845, the Stabskapitän Ismail Khan was appointed by the highest order to be in the army cavalry at the Russian Caucasus Forces. On 19 September 1847, he was appointed head of the Kengerly Cavalry. For distinction in service on 5 February 1853, he was promoted to captain.

On 16 October 1853, the Crimean War began. On 10 November, Ismail Khan was appointed head of the Erivan Bek squad, which became part of the Erivan detachment of the Russian troops. From 1 May to 5 December 1854, he was assistant commander of the 4th Muslim Cavalry Regiment. From 22 April to 5 July he took part in the clashes in the region of Igdyr, Caravanserai, Orgov. On 17 July, as part of the Erivan detachment, under the general commandment of the Lieutenant General Baron Karl Karlovich Wrangel, he participated in the defeat of the 12 thousand corps of Selim Pasha on the Chingil Heights and the subsequent occupation of Bayazet on 19 July. Later he took part in the actions of the area Abas-gel, Mysun, Dutakh, Diadin, Kara-kilis, Alashkert (Toprak-kala), etc. For military merits, on 4 August 1855, he was transferred to the Cossack Life Guards. On 13 October 1856, he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislaus of the 3rd degree with swords.

On 3 April 1860, Ismail Khan was promoted to colonel. On 22 September 1867, the Colonel Ismail Khan was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir of the 4th degree with a bow by the highest order for seniority in the officer ranks of 25 years of the guard. In January 1868, by the Shakh of Qajar dynasty, he was awarded the Order of the Lion and the Sun of the 2nd degree with a star. On 28 September 1872, “for distinction in service”, he was awarded the Order of St. Stanislaus of the 2nd degree with the imperial crown.

Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski became famous during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). On 17 April 1877, the troops of the Erivan detachment under the general commandment of the Lieutenant General Arshak Ter-Gukasov crossed the Russian-Turkish border and reached Bayazet through the Chingil Pass. The Turks, having learned about the approach of large forces of the Russian troops, left the fortress. On 18 April, Bayazet was occupied by a small detachment led by the Lieutenant Colonel A. Kovalevsky, the commander of the 2nd battalion of the 74th Stavropol Infantry Regiment of the 19th Infantry Division. Kovalevsky was appointed commander of the Bayazet District. The main forces of the Erivan detachment continued to move deep into the enemy’s territory. On 24 May, the Lieutenant Colonel Kovalevsky, as commander of the district troops, was replaced by the Lieutenant Colonel G. Patsevich, who arrived in Bayazet with replenishment from two companies of the 73rd Crimean Infantry Regiment of the same division. The Captain F. E. Stokvich was appointed the commandant of the fortress.

On 5 May 1877, by the order of the commander-in-chief of the Caucasian Army, the Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich of Russia, the Colonel Ismail Khan was appointed commander of the newly formed Erivan Equestrian Irregular Regiment. The regiment became part of the cavalry irregular brigade of the Major General Kelbali Khan Nakhchivanski, the younger brother of Ismail Khan. The brigade had the task of covering the state border from an eventual invasion of the enemy into the territory of the Erivan province.

On 4 June, the Major General Kelbali Khan, having received the information from the Lieutenant Colonel Patsevich about the movement of the Turks from Van to Bayazet, turned to the head of the Erivan detachment, the General Tergukasov, for permission to send reinforcements to Bayazet’s garrison, but he was refused. The next day Patsevich informed Kelbali Khan that the Turkish cavalry was reconnoitring the roads to Bayazet, and asked for help. Kelbali Khan again appealed to the General Ter-Gukasov for permission and this time the corresponding order was received. On the same day, 5 June, the General Kelbali Khan sent 300 of the Erivan Irregular Equestrian Regiment headed by Ismail Khan to Bayazet. On 6 June, the Lieutenant Colonel Patsevich decided to conduct reconnaissance, and set out with two companies of infantry under the commandment of the Lieutenant Colonel Kovalevsky and one hundred Cossacks from the fortress to Van. Faced with many times superior enemy troops, Patsevich’s detachment, suffering serious losses, began to retreat to the fortress. The Lieutenant Colonel Kovalevsky was seriously wounded and died on a stretcher. A critical situation has arisen. At that moment, hundreds of the Erivan irregular cavalry regiment, led by Ismail Khan approached Bayazet after many hours of march. With his fighters, Ismail Khan entered into an unequal battle with the superior forces of the enemy.

From the report of the commandant of Bayazet, the captain F. E Shtokvich, to His Imperial Highness, the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army, the Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, dated with 4 July 1877, No. 116:

From the report of the commandant of Bayazet, the captain F. E Shtokvich, to His Imperial Highness, the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army, the Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, dated with 4 July 1877, No. 116:

The enemy, up to 7 thousand in number, makes a roundabout movement along the ridge of Kizil-dag in order to cut off our retreat to the city. Ismail Khan made a quick movement to the left, hurried his hundreds and, having taken a good position, stopped the roundabout movement with well-aimed fire, holding the enemy for two hours … – from the report of the commandant of the city of Bayazet, the captain Stockvich

When the retreating column, firing back, approached the fortress gate, it was blocked by a large herd of donkeys laden with breadcrumbs, since the fortress food master decided to move his warehouses from the city to the citadel on that very day. There was a great confusion under the deadly fire of the enemy, which led to heavy human and material losses – all the provisions, donkeys, Cossacks’ horses, and the militiamen were captured by the enemy. Despite the heavy losses, the surviving part of Patsevich’s detachment and the hundreds of remnants of Ismail Khan still managed to retreat to the citadel under the protection of the fortress walls. The garrison of the fortress consisted of six infantry companies, three hundred Cossacks, two guns and the remnants of the Erivan irregular equestrian regiment. In total, taking into account the losses incurred, about 1 500 people. The citadel was not prepared for the siege, since the commandant of the fortress did not give timely orders for the creation of water supplies, and placed the garrison’s food warehouse in the city, and provisions were delivered to the citadel as needed. The besiegers took a stream from which water was piped into the fortress. Provisions remained for no more than three days. In such conditions, the 23-day defence of the Bayazet fortress began, which lasted from 6 to 28 June and went down in history as the “Bayazet seat”. From Ismail Khan’s reminiscences:

There was no positive information about Tergukasov’s detachment; on the contrary, rumours penetrated into the garrison that it was surrounded and almost destroyed, which took away any hope for the outside help, and, of course, could influence the mood of the people to a certain extent …In the conversations with me, the Lieutenant Colonel Patsevich and two or three other people have repeatedly spoken out in the sense that the outcome of our staying can only be inevitable death, if we do not capitulate.

Of course, I did not deny the possibility of such an end, but I always repeated at the same time that I would never agree to capitulate Bayazet also because I am a Muslim. I know that the capitulation would be attributed to this very circumstance, even if a thousand of other reasons were prompted for it …

— “Defence of Bayazet – the story of the Lieutenant-General Khan Nakhchivanski”, the newspaper “Caucasus”, 12 April 1895

On the third day of the blockade, the heat, thirst and hunger began to drive the besieged into despair. The officers and lower ranks gathered in groups and discussed the situation. Voices began to be heard calling for capitulation. From Ismail Khan’s reminiscences:

The faces of the speakers were gloomy. The listeners looked no less stern.

– It could have happened worse! – Suddenly exclaimed a young artillery officer, who was standing in the crowd with others, but whose name, unfortunately, I do not remember.

– After all, three times do not die?! We will fight as long as our legs are holding us, and there, that God will send us!

I silently stretched out my hand to this officer and told the others that the main things are not to lose heart and not to lose hope, since they will help us out, noI silently stretched out my hand to this officer and told the others that the main things are not to lose heart and not to lose hope, since they will help us out, no matter what …

— Defense of Bayazet – the story of the Lieutenant-General Khan Nakhchivanski”, the newspaper “Caucasus”, 12 April 1895

The young artillery officer, whom the Colonel Ismail Khan recalled, was the commander of the 4th platoon of the 4th battery of the 19th artillery brigade, the Lieutenant Nikolai Konstantinovich Tomashevsky (later artillery General).

On the morning of 8 June, the Turks, in large forces under the leadership of the former commandant of the city Kamal Ali Pasha, launched a powerful attack on the citadel. Succumbing to panic, the Lieutenant Colonel Patsevich, with the consent of a number of other officers, including the fortress commandant Shtokvich, decided to surrender Bayazet. The fire was stopped and a white flag was raised over the walls of the fortress. Ismail Khan at that time was near his seriously wounded son, the Praporshchik of the Erivan Equestrian Irregular Regiment Amanullah Khan Nakhchivanski. The fact that a white flag was raised over Bayazet was informed by the Lieutenant Tomashevsky. From Ismail Khan’s reminiscences:

… Suddenly an artillery officer, about whom I spoke earlier, rushed in. He was agitated.

– Colonel, the fortress is surrendering! He exclaimed. – What do you say? How do they hand it over?! – I jumped up as if stung. – Patsevich raised a white flag and a huge mass of Turks has already rushed to our gate, – the officer explained. After that, I jumped out into the courtyard, where a crowd of officers and soldiers was gathered, and I really saw: a white flag fluttering high on a huge pole attached to the wall of the citadel, and Patsevich and several other officers were standing nearby. – Gentlemen, what are you doing?! … – I shouted. “Did we take an oath to dishonour ourselves and the Russian weapons with a faint-hearted capitulation?! … It’s a shame! …

As long as there is even a drop of blood in our veins, we are obliged to fight and defend Bayazet in front of the Tsar! … Whoever decides to act differently is a traitor, and that I will order to be shot immediately! Down with the flag, shoot guys!

– “Defense of Bayazet – the story of the Lieutenant-General Khan Nakhchivanski”, the newspaper “Caucasus”, 12 April 1895.

From that moment, in fact, having dismissed the Lieutenant Colonel Patsevich, the Colonel Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski, as a senior in rank, on his own initiative, took over the commandment of Bayazet’s garrison. Shooting resumed, and Patsevich was one of the first to be mortally wounded, and he was wounded in the back. According to some reports, the shot was fired by one of the garrison’s officers. After the white flag was torn down and the attack of the Turks was repulsed, Ismail Khan appointed the military foreman of the 2nd Khopersky Regiment of the Kuban Cossack Army, Olympiy Nikitich Kvanin, as his assistant in carrying out all orders for the defence of Bayazet. Having assumed the command of the garrison, Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski organized the defence of the fortress and in difficult conditions, without water and provisions, held it until the main forces of the Russian army approached. When another envoy who arrived at the citadel, one who fled to the enemy after the start of the war, told Ismail Khan that if the garrison did not capitulate, would be hanged, Ismail Khan replied that the envoy himself would be hanged first as a traitor, and this order was immediately carried out. By the highest order of 19 December 1877, “for military distinction”, he was awarded the rank of Major General, and on 31 December 1877, “for exemplary and bravery management shown during the blockade of Bayazet in June 1877”, he was awarded the Order of the “Saint Great Martyr and Victorious George of the IV degree”.

On 28 October 1890 was marked the 50th anniversary of Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski’s service in the officer ranks. On this day, the hero received numerous congratulations. From a telegram from the Minister of War:

“The Sovereign Emperor, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of your service in the officer ranks, has most mercifully deigned you to be promoted to Lieutenant General, with the retention of the Caucasian Military District with the troops and with the increased salary according to the rank of 2,034 rubles a year. Congratulations, Your Excellency, with the Monarch’s Grace and Happy Anniversary. The Minister of War, the Adjutant General Vannovsky.”

From the telegram of the Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich:

To the Lieutenant General Ismail Khan. I congratulate you on this significant day of your life and thank you for your service under My commandment. Mikhail.

On 14 June 14 1908, at the age of 89, Ismail Khan applied for his resignation to Nicholas II. On 18 August 1908, the Emperor, taking into account the “very long and military service of the Lieutenant General Ismail Khan,” by the Imperial Order promoted him to the rank of General to the General of the cavalry with dismissal from service with the uniform and pension.

During his service, Ismail Khan became the Knight of the Orders of St. George the Victorious of the 4th degree, St. Vladimir of the 2nd, 3rd degree, and 4th degree with a bow, St. Anne of the 1st degree, St. Stanislaus of the 1st and 2nd degree with the Imperial Crown of the 3rd degree with swords. He was Highly allowed to accept and wear the Persian Orders of the Lion and the Sun of the 1st, 2nd, and the 3rd degree, with the Star. He has been awarded many medals. The hero of Bayazet’s defence, the Cavalry General Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski, died on 10 February 1909 in his hometown – Nakhichevan. At the funeral at the head of the general there were 14 pillows with orders.

The personality of Ismail Khan again attracted the attention after the release of the TV series “Bayazet” based on the novel of the same name by Valentin Pikul, where Ismail Khan was presented in a negative light.

Military ranks

- Entered the service (1 May 1839)

- Praporshchik (28.10.1840)

- Lieutenant (20.03.1844)

- Stabskapitän (30.08.1847)

- Captain (05.02.1853)

- Rittmeister (04.08.1855)

- Colonel (03.04.1860)

- Major general (19.12.1877)

- Lieutenant general (28.10.1890)

- General of the cavalry (18.08.1908)

Awards

Russian:

- Order of the St. Stanislaus of the 3rd degree with swords (1856)

- Order of the St. Vladimir of the 4th degree with a bow for 25 years in the officer ranks (1867)

- Order of the St. Stanislaus of the 2nd degree with the imperial crown (1872)

- Order of the St. George of the 4th degree (31 December 1877)

- Order of the St. Vladimir of the 3rd degree (1883)

- Order of the St. Stanislaus of the 1st degree (1888)

- Order of the St. Anne of the 1st degree (1901)

- Order of the St. Vladimir of the 2nd degree (1907)

- Medal “In Memory of the War of 1853-1856”

- Medal “In memory of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878.”

- Medal “In commemoration of the Emperor Alexander III reign”

- Medal “In memory of the Emperor Nicholas I reign”

Qajar dynasty:

- Order of the Lion and the Sun of the 3rd degree with diamonds (1846)

- Order of the Lion and the Sun of the 2nd degree with star (1868)

- Order of the Lion and the Sun of the 1st degree (1903)

Life and family

He was married the first time to Khanym-Jan Khanum (about 1819 -?), the daughter of the Kengerli tribe head, Novruz Agha. His second marriage was to Shovket Khanum, the daughter of Abbas-Quli Khan Erivanski. He had nine children:

The eldest son – Amanullah Khan Nakhchivanski (15 June 1845 – around 1891) – entered the service on 6 May 1865 in His Majesty’s Own Squire Convoy. On 1 November 1865, he was promoted to cadet. Upon completion of the established period of service, on 21 August 1869, he was promoted to militia ensign with the status of army cavalry. He was awarded with a silver medal “For service in the Convoy of the Sovereign Emperor Alexander Nikolaevich” on the Anninskaya ribbon to be worn around the neck. After the start of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878, he is enlisted in the newly formed Erivan Equestrian Irregular Regiment. On 6 June 1877, in a battle near Bayazet, he was seriously wounded. He is a participant of the 23-day “Bayazet seat.” On 19 June of the same year, “According to the Imperial Power represented by His Imperial Highness, the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army, he was awarded the Order of the St. Anna of the 3rd degree with swords and a bow.” On 19 December 1877, he was enlisted in the Life Guards Cossack Regiment as a cornet by an Imperial Order. On 28 March 1882, the Cornet of the Life Guards of the Cossack Regiment, Amanulla KhanNakhchivanski, which was at the disposal of the Headquarters of the Caucasian Military District, was promoted to lieutenant by an Imperial Order. On 9 April 1889, by the highest order, he was promoted to staff-captain. He was married to the daughter of the Major General Prince Khasay Khan Utsmiyev and the famous Azerbaijani poet Khurshidbanu Begum “Natavan”, the Princess Khanbika Khanum Utsmiyeva (1855-1921).

Eldest daughter – Tarlan Khanum (13 October 1848-?). She was married to Abbas Quli Khan Erivanski.

Khadyr Khanum (15 July 1850-?)

Bahman Khan (2 September 1851-?)

Habib Ulla Khan (17 October 1852-?). He was married to the Princess Navwab Agha Khanum, the daughter of the Prince Bahman Mirza Qajar.

Soltanat Khanum (20 October 1855-?)

Aziz Khan I (15 May 1857-?)

Sona Begum (20 February 1859-?)

Aziz Khan II (15 January 1860 – 10 April 1883). Militia Praporshchik officer.

Amanullah Mirza Qajar

Amanullah Mirza Qajar (Russian: Аманулла Мирза Каджар; Persian: امان الله میرزا قاجار; 1857—1937) was a prince in Persia’s Qajar dynasty. He was also an Imperial Russian and Azerbaijani military commander, obtaining the rank of Major General.

Аманулла Мирза Каджар

امان الله میرزا قاجار

Bahman Mirza’s son in Karabakh

Born: 8 January 1857, Shusha, Russian Empire

Died: 1937, Tehran, Iran

Allegiance: Russia Russian Empire, Azerbaijan ADR, State flag of Iran (1907-1933).svg Persia

Service/branch: Infantry

Years of service: 1879—1920

Rank: Major General

Battles/wars: Russo-Japanese War, First World War, Armenian-Azerbaijani War

Early life

Amanullah Mirza Qajar was born on January 8, 1857 in the city of Shusha in the Russian Empire (modern day Azerbaijan.) He was the 17th son of Prince Bahman Mirza Qajar of Persia by one of the latter’s junior wives. His Russian family name was Persidskii (literally, “of Persia.”)

Russian Army

Qajar entered military service on July 19, 1879, in the 164th Infantry Regiment Zagatala. In 1883, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant. On November 20, 1886, he was transferred to the 2nd Battalion plastun of the Kuban Cossacks. On May 9, 1902, Qazar was promoted to yesaul. On April 16, 1909, he became the Army yesaul-commander of the 9th Battalion of the Kuban plastun.

First World War

During World War I, Qajar fought on the Austrian front. He was awarded the Order of St. Anne 2nd Class with swords, the Order St. Vladimir 3rd Class with swords, and the Order St. Stanislaus 3rd Class. On April 25, 1915, he was promoted to colonel. Because of a severe leg wound, Amanullah was sent to the rear for treatment. In 1916, he returned to the front. Along with his battalion, he fought near the village of Marhonovka. Qajar captured the enemy trenches and destroyed the enemy’s manpower. During the operations on November 5, 1916, he was awarded the Saint George Sword. He received the rank of Major General in 1917. After the February Revolution, he lived in Tbilisi and Shusha.

Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

After the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) created its first army as a newly established state, Qajar filed a report on December 1, 1918, to the newly established Ministry of War with a request of admission to their armed forces. In March 1919 he was a part of the emergency diplomatic mission of the Republic of Azerbaijan and participated in the Persian government in Tehran. He served as chairman of the central military service presence. On January 27, 1920, Major General Qajar was appointed as the deputy chief of the 1st Infantry Division of the ADR and head of the garrisons in Khankendi and Shusha. He participated in fighting the attacks of the Armenian armed forces on the military units of the ADR on 22–23 March 1920.

Iran

After the fall of the ADR in connection with the repression of the Bolsheviks, Amanullah was forced to leave for Iran. Living in Tehran, he taught at the military school and participated in the formation of the Iranian army. He was a deputy of the Majlis (Parliament) of Iran, and the chairman of the society of the Iranian-Soviet friendship. He died in 1937 in Tehran.

Aleksander Reza Qoli Mirza Qajar

Aleksander Petrovich Reza Qoli Mirza Qajar (Russian: Александр Петрович Риза-Кули Мирза Каджар; Persian: الکساندر پتروویچ رضا قلی میرزا قاجار; May 25, 1869 -?) – was a prince of Persia’s Qajar dynasty, an Imperial Russian military leader and the commander of Yekaterinburg (1918), having the rank of Colonel (Polkovnik).

**Aleksander Petrovich Reza-Qoli-Mirza Qajar

Александр Петрович Риза-Кули Мирза Каджар

Born: 25 May 1869, Saint Petersburg Governorate, Russian Empire

Died: Unknown

Allegiance: Russia Russian Empire

Rank: Colonel (Polkovnik)

Biography

Alexander Petrovich Reza Qoli Mirza Qajar was born on May 25, 1869 in the Saint Petersburg Governorate. According to the track record, he was “the son of the Prince of Persia, a native of St. Petersburg Province and had the Orthodox religion.” In 1890–1893 he completed his military education at Vilnius Military School.

Khurshid Qajar née Nakhchivanskaya

Birth name: Khurshid Nakhchivanskaya

Born: 1894, Nakhchivan, Russian Empire

Died: Summer 1963 (aged 69), Baku, Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic

Genres: Opera

Occupation(s): Opera singer

She was married to Feyzullah Mirza Qajar until 1920. Her second husband was Count Nikolai Nikolaievich Khudyakov. She had a son from her first marriage – Shafi, named after Shafi Khan Qajar, she had adoptive children from second marriage Nadir Aliyev-Khudyakov, Adelia Aliyeva-Khudyakova and Marina Khudyakova.

The Bahmani family

Brahmani family, also Bahmani-Qajar is an aristocratic Iranian family belonging to one of the princely families of the Qajar dynasty, the ruling house that reigned Iran 1785–1925.

Heirlooms: Treasury of Bahman Mirza

Parent family: Qajar dynasty

The Bahmani family, also Bahmani-Qajar is an aristocratic Iranian family belonging to one of the princely families of the Qajar dynasty, the ruling house …

Connected families: Nakhchivanski; Talishkhanovs; Badalbayli family; Mehmandarov …

Parent family: Qajar dynasty

Heirlooms: Treasury of Bahman Mirza

The Qajar imperial dynasty

The Qajar dynasty (audio speaker iconlisten (help·info); Persian: سلسله قاجار Selsele-ye Qājār, Azerbaijani: Qacarlar قاجارلر) was an Iranian royal dynasty of Turkic origin, specifically from the Qajar tribe, ruling over Iran from 1789 to 1925. The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf ‘Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease, putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty, and Mohammad Khan was formally crowned as Shah after his punitive campaign against Iran’s Georgian subjects. In the Caucasus, the Qajar dynasty permanently lost many of Iran’s integral areas to the Russians over the course of the 19th century, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Kangarli Tribe

The Kangarlis were the ancient Turkic tribe. The word “Kangar” emerged after the occupation of the Kang state between the Aral and Balkhash lakes by the Huns in the III century. A part of the Kangarlis joined the Huns came from the North Caucasus to Azerbaijan in the IV-V centuries. There are reports that the Kangarlis were living in Azerbaijan, particularly in Nakhchivan after that period. Kangarli’s tribe had a history of 6,000 years, and their names were first mentioned in connection with the Sumerians. The Sumerians’ name was Kangar. Today’s Persian Gulf was called the Gulf of Kangar for centuries. The Kangarlis established the Kang state in Central Asia (IV century), the state of Sallarids in Azerbaijan (X century) and the Nakhchivan khanate (XVIII century). In the “Book of Dada Gorgud”, Kangarli is called as “Kanqali”. The Kangarlis were involved in the ethnogeny of the Azerbaijani people. From the second half of the XVIII century Kangarli rulers had high ranks and they ruled the Nakhchivan khanate, one of the strongest khanates of Azerbaijan. Although the Nakhchivan khanate was ceded to Russia under the Turkmenchay Treaty in 1828, the authorities of the Kangarlis were continuing to hold positions with the title of “Naib” until 1840. A part of the Kangarli tribe was given the Nakhchivanski surname during the Russian Empire. There are a number of prominent socio-political and military figures, scientists and cultural workers among the Kangarlis. The names of the six generals of the Kangarli tribe are known in the history of the Azerbaijani military.

Heyran and Gonchabayim Kangarli, the prominent representatives of Azerbaijan’s classical poetry, were Azerbaijani poets who lived and worked in the XIX century. Bahruz Kangarli, who was among the first Azerbaijanis who received specialized education in the XX century, also served the creation of different genres in our national painting and enrichment with new artistic means of expression.

Maku Khanate

It came into existence after the death of Nader Shah which led to the breakup of the Safavid empire, and gain semi-independence It rejoined the Persian Empire in 1829, however was not abolished for another century after the death of Murtuzaqulu Khan Bayat.

Qizilbash or Kizilbash

Qizilbash or Kizilbash (Ottoman Turkish: قزيل باش; Turkish: Kızılbaş, lit. ’Red head’ Turkish pronunciation: Azerbaijani: Qızılbaş, Persian: قزلباش, romanized: Qezelbāš) were a diverse array of mainly Turkoman Shia militant groups that flourished in Iranian Azerbaijan, Anatolia, Armenian Highlands, Caucasus, and Kurdistan from the late 15th century onwards, and contributed to the foundation of the Safavid dynasty of Iran.

The word Qizilbash derives from Turkish Kızılbaş, meaning “red head”. The expression is derived from their distinctive twelve-gored crimson headwear (tāj or tark in Persian; sometimes specifically titled “Haydar’s Crown” تاج حیدر / Tāj-e Ḥaydar), indicating their adherence to the Twelve Imams and to Shaykh Haydar, the spiritual leader (sheikh) of the Safavid order in accordance with the Imamate in Twelver doctrine. The name was originally a pejorative label given to them by their Sunni Ottoman foes, but soon it was adopted as a provocative mark of pride.

The origin of the Qizilbash can be dated from the 15th century onward, when the spiritual grandmaster of the movement, Shaykh Haydar (the head of the Safaviyya Sufi order), organized his followers into militant troops.

Connections between the Qizilbash and other religious groups and secret societies, such as the Iranian Zoroastrian Mazdaki movement in the Sasanian Empire, or its more radical offspring, the Persian Khurramites, and Turkish shamanism, have been suggested. Of these, the Khurramites were, like the Qizilbash, an early Shi’i ghulat group and dressed in red, for which they were termed “the red ones” (Persian: سرخجامگان,Arabic: محمرة muḥammirah) by medieval sources. In this context, Turkish scholar Abdülbaki Gölpinarlı sees the Qizilbash as “spiritual descendants of the Khurramites”.

The Qizilbash were a coalition of many different tribes of predominantly (but not exclusively) Turkic-speaking background united in their adherence to Safavi Shia Islam.

As murids (sworn students) of the Safavi sheikhs (pirs), the Qizilbash owed implicit obedience to their leader in his capacity as their murshid-e kāmil “supreme spiritual director” and, after the establishment of the kingdom, as their padishah (great king). The establishment of the kingdom thus changed the purely religious pir – murid relationship into a political one. As a consequence, any act of disobedience of the Qizilbash Sufis against the order of the spiritual grandmaster (Persian: nāsufigari “conduct unbecoming of a Sufi”) became “an act of treason against the king and a crime against the state”, as was the case in 1614 when Padishah Abbas the Great put some followers to death.t

For the surname, see Qizilbash (name). For the related tariqa that led to the Safavid dynasty, see Safaviyya. For the related Bāṭenī Imāmī-Tasawwufī Ṭarīqah in Turkey, see Alevism. For the suburb of Nicosia, Cyprus but under de facto control of Northern Cyprus, see Kizilbash.

Etymolog

Mannequin of a Safavid Qizilbash soldier, exhibited in the Sa’dabad Complex, Iran

The word Qizilbash derives from Turkish Kızılbaş, meaning “red head”. The expression is derived from their distinctive twelve-gored crimson headwear (tāj or tark in Persian; sometimes specifically titled “Haydar’s Crown” تاج حیدر / Tāj-e Ḥaydar), indicating their adherence to the Twelve Imams and to Shaykh Haydar, the spiritual leader (sheikh) of the Safavid order in accordance with the Imamate in Twelver doctrine. The name was originally a pejorative label given to them by their Sunni Ottoman foes, but soon it was adopted as a provocative mark of pride.

Origins

The origin of the Qizilbash can be dated from the 15th century onward, when the spiritual grandmaster of the movement, Shaykh Haydar (the head of te Safaviyya Sufi order), orgnized his followers into militant troops.

Connections between the Qizilbash and other religious groups and secret societies, such as the Iranian Zoroastrian Mazdaki movement in the Sasanian Empire, or its more radical offspring, the Persian Khurramites, and Turkish shamanism, have been suggested. Of these, the Khurramites were, like the Qizilbash, an early Shi’i ghulat group and dressed in red, for which they were termed “the red ones” (Persian: سرخجامگان,Arabic: محمرة muḥammirah) by medieval sources. In this context, Turkish scholar Abdülbaki Gölpinarlı sees the Qizilbash as “spiritual descendants of the Khurramites”.

Organization

The Qizilbash were a coalition of many different tribes of predominantly (but not exclusively) Turkic-speaking background united in their adherence to Safavi Shia Islam.

As murids (sworn students) of the Safavi sheikhs (pirs), the Qizilbash owed implicit obedience to their leader in his capacity as their murshid-e kāmil “supreme spiritual director” and, after the establishment of the kingdom, as their padishah (great king). The establishment of the kingdom thus changed the purely religious pir – murid relationship into a political one. As a consequence, any act of disobedience of the Qizilbash Sufis against the order of the spiritual grandmaster (Persian: nāsufigari “conduct unbecoming of a Sufi”) became “an act of treason against the king and a crime against the state”, as was the case in 1614 when Padishah Abbas the Great put some followers to death.

Beliefs

The Qizilbash adhered to heterodox Shi’i doctrines encouraged by the early Safavi sheikhs Haydar and his son Ismail I. They regarded their rulers as divine figures, and so were classified as ghulat “extremists” by orthodox Twelvers.

When Tabriz was taken, there was not a single book on Twelverism among the Qizilbash leaders. The book of the well known Iraqi scholar al-Hilli (1250–1325) was procured in the town library to provide religious guidance to the state. The imported Shi’i ulama did not participate in the formation of Safavid religious policies during the early formation of the state. However, ghulat doctrines were later forsaken and Arab Twelver ulama from Lebanon, Iraq, and Bahrain were imported in increasing numbers to bolster orthodox Twelver practice and belief.

Qizilbash aqidah in Anatolia

In Turkey, orthoprax Twelvers following Ja’fari jurisprudence are called Ja’faris. Although the Qizilbash are also Twelvers, their practices do not adhere to Ja’fari jurisprudence.

The Qizilbash have a unique and complex conviction tracing back to the Kaysanites and Khurramites, who are considered ghulat (extremist) Shia. According to Turkish scholar Abdülbaki Gölpinarli, the Qizilbash of the 16th century – a religious and political movement in Iranian Azerbaijan that helped to establish the Safavid dynasty – were “spiritual descendants of the Khurramites”.

Among the individual revered by Alevis, two figures, firstly Abu Muslim who assisted the Abbasid Caliphate to beat Umayyad Caliphate, but who was later eliminated and murdered by Caliph al-Mansur, and secondly Babak Khorramdin, who incited a rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate and consequently was killed by Caliph al-Mu’tasim, are highly respected. In addition, the Safavid leader Ismail I is highly regarded.

The Qizilbash aqidah, or creed, is based upon a syncretic fiqh (jurisprudence tradition) called batiniyya, referring to an inner or hidden meaning in holy texts. It incorporates some Qarmatian thoughts, originally introduced by Abu’l-Khāttāb Muhammad ibn Abu Zaynab al-Asadī, and later developed by Maymun al-Qāddāh and his son ʿAbd Allāh ibn Maymun, and Muʿtazila with a strong belief in The Twelve Imams.

Not all of the members believe that the fasting in Ramadan is obligatory although some Alevi Turks perform their fasting duties partially in Ramadan.

Some beliefs of shamanism still are common among the Qizilbash in villages.

The Qizilbash are not a part of Ja’fari jurisprudence, even though they can be considered as members of different tariqa of Shia Islam all looks like sub-classes of Twelver. Their conviction includes Batiniyya-Hurufism and “Sevener-Qarmatians-Isma’ilism” sentiments.

They all may be considered as special groups not following the Ja’fari jurisprudence, like Alawites who are in the class of ghulat Twelver Shia Islam, but a special Batiniyya belief somewhat similar to Isma’ilism in their conviction.

"Turk & Tājīk"

Shah Ismail I, the Sheikh of the Safavi tariqa, founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, and the Commander-in-chief of the Qizilbash armies.

Among the Qizilbash, Turcoman tribes from Eastern Anatolia and Iranian Azerbaijan who had helped Ismail I defeat the Aq Qoyunlu tribe were by far the most important in both number and influence and the name Qizilbash is usually applied exclusively to them.Some of these greater Turcoman tribes were subdivided into as many as eight or nine clans, including:

Ustādjlu (Their origins reach back to the Begdili)

Rūmlu

Shāmlu (the most powerful clan during the reign of Shah Ismail I.)

Dulkadir (Arabic: Dhu ‘l-Kadar)

Afshār

Qājār

Takkalu

Other tribes – such as the Turkman, Bahārlu, Qaramānlu, Warsāk, and Bayāt – were occasionally listed among these “seven great uymaqs”. Today, the remnants of the Qizilbash confederacy are found among the Afshar, the Qashqai, Turkmen, Shahsevan, and others.

Some of these names consist of a place-name with the addition of the Turkish suffix -lu, such as Shāmlu or Bahārlu. Other names are those of old Oghuz tribes such as the Afshār, Dulghadir, or Bayāt, as mentioned by the medieval Karakhanid historian Mahmud al-Kashgari.

The non-Turkic Iranian tribes among the Qizilbash were called Tājīks by the Turcomans and included

Tālish

The Lurs

Siāh-Kuh (Karādja-Dagh)

certain Kurdish tribes

certain Persian families and clans

The rivalry between the Turkic clans and the Persian nobles was a major problem in the Safavid kingdom. As V. Minorsky put it, friction between these two groups was inevitable, because the Turcomans “were no party to the national Persian tradition”. Shah Ismail tried to solve the problem by appointing Persian wakils as commanders of Qizilbash tribes. The Turcomans considered this an insult and brought about the death of 3 of the 5 Persians appointed to this office – an act that later inspired the deprivation of the Turcomans by Shah Abbas I.

Persian miniature created by Mo’en Mosavver, depicting Shah Ismail I at an audience receiving the Qizilbash after they defeated the Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar. Album leaf from a copy of Bijan’s Tarikh-i Jahangusha-yi Khaqan Sahibqiran (A History of Shah Ismail I), produced in Isfahan, end of the 1680s.

History

Beginnings

The rise of the Ottomans put a great strain on the Turkmen tribes living in the area, which eventually led them to join the Safavids, who transformed them into a militant organisation, called the Qizilbash (meaning “red heads” in Turkish), initially a pejorative label given to them by the Ottomans, but later adopted as a mark of pride.The religion of the Qizilbash resembled much more the heterodox beliefs of northwestern Iran and eastern Anatolia, rather than the traditional Twelver Shia Islam. The beliefs of the Qizilbash consisted of non-Islamic aspects, varying from crypto-Zoroastrian beliefs to shamanistic practises, the latter which had been practised by their Central Asian ancestors.

However, a common aspect that all these heterodox beliefs shared was a form of messianism, devoid of the restrictions of the Islam practiced in urban areas. Concepts of divine inspiration and reincarnation were common, with the Qizilbash viewing their Safavid leader (whom they called morshed-e kamel, “the Perfect Guide”) as the reincarnation of Ali and a manifestation of the divine in human form. The were a total of seven major Qizilbash “tribes”, each named after an area they identified themselves with; the Rumlu presumably came from Rum (Anatolia); the Shamlu from Sham (Syria); the Takkalu from the Takkeh in southeastern Anatolia; the Ostajlu from Ostaj in the southern Caucasus. It is uncertain if the Afshar and Qajar were named after an area in Azerbaijan, or after their ancestors. All these tribes shared a common lifestyle, language, faith, and animosity towards the Ottomans.

In the 15th century, Ardabil was the center of an organization designed to keep the Safavi leadership in close touch with its murids in Azerbaijan, Iraq, Eastern Anatolia, and elsewhere. The organization was controlled through the office of khalīfāt al-khulafā’ī who appointed representatives (khalīfa) in regions where Safavi propaganda was active. The khalīfa, in turn, had subordinates termed pira. The Safavi presence in eastern Anatolia posed a serious threat to the Ottoman Empire because they encouraged the Shi’i population of Asia Minor to revolt against the sultan.

In 1499, Ismail, the young leader of the Safavi order, left Lahijan for Ardabil to make a bid for power. By the summer of 1500, about 7,000 supporters from the local Turcoman tribes of Asia Minor (Anatolia), Syria, and the Caucasus – collectively called “Qizilbash” by their enemies – rallied to his support in Erzincan. Leading his troops on a punitive campaign against the Shīrvanshāh (ruler of Shirvan), he sought revenge for the death of his father and his grandfather in Shīrvan. After defeating the Shīrvanshāh Farrukh Yassar and incorporating his kingdom, he moved south into Azarbaijan, where his 7,000 Qizilbash warriors defeated a force of 30,000 Aq Qoyunlu under Alwand Mirzā and conquered Tabriz. This was the beginning of the Safavid state.

By 1510, Ismail and his Qizilbash had conquered the whole of Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan, southern Dagestan (with its important city of Derbent), Mesopotamia, Armenia, Khorasan, Eastern Anatolia, and had made the Georgian kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti his vassals. Many of these areas were priorly under the control of the Ak Koyunlu.

In 1510 Shah Ismail sent a large force of the Qizilbash to Transoxiania to fight the Uzbeks. The Qizilbash defeated the Uzbeks and secured Samarkand at the Battle of Marv. However, in 1512, an entire Qizilbash army was annihilated by the Uzbeks after Turcoman Qizilbash had mutinied against their Persian wakil and commander Najm-e Thani at the Battle of Ghazdewan. This defeat put an end to Safavid expansion and influence in Transoxania and left the northeastern frontiers of the kingdom vulnerable to nomad invasions, until some decades later.

Battle of Chaldiran

Meanwhile, the Safavid dawah continued in Ottoman areas – with great success. Even more alarming for the Ottomans was the successful conversion of Turcoman tribes in Eastern Anatolia, and the recruitment of these well experienced and feared fighters into the growing Safavid army. In order to stop the Safavid propaganda, Sultan Bayezid II deported large numbers of the Shi’i population of Asia Minor to Morea. However, in 1507, Shah Ismail and the Qizilbash overran large areas of Kurdistan, defeating regional Ottoman forces. Only two years later in Central Asia, the Qizilbash defeated the Uzbeks at Merv, killing their leader Muhammad Shaybani and destroying his dynasty. His head was sent to the Ottoman sultan as a warning.

A Safavid Qizilbash cavalryman

In 1511, a pro-Safavid revolt known as the Shahkulu Uprising broke out in Teke. An imperial army that was sent to suppress it, was defeated. Shah Ismail sought to turn the chaos within the Ottoman Empire to his advantage and moved up his borders even more westwards in Asia Minor. The Qizilbash defeated a large Ottoman army under Sinan Pasha. Shocked by this heavy defeat, Sultan Selim I (the new ruler of the Empire) decided to invade Persia with a force of 200,000 Ottomans and face the Qizilbash on their own soil. In addition, he ordered the persecution of Alevis and massacre its adherents in the Ottoman Empire.

On 20 August 1514 (1st Rajab 920 A.H.), the two armies met at Chaldiran in northwestern Iran. The Ottomans -equipped with both firearms and cannon- were reported to outnumber the Qizilbash as much as three to one. The Qizilbash were badly defeated; casualties included many high-ranking Qizilbash amirs as well as three influential ulamā.

The defeat destroyed Shah Ismail’s belief in his own invincibility and divine status. It also fundamentally altered the relationship between the murshid-e kāmil and his murids (followers).

The deprivation of the Turcomans

Ismail I tried to reduce the power of the Turcomans by appointing Iranians to the vakil office. However, the Turcomans did not like having an Iranian to the most powerful office of the Safavid Empire and kept murdering many Iranians who were appointed to that office. After the death of Ismail, the Turkomans managed to seize power from the Iranians, they were however, defeated by Tahmasp I, the son of Ismail.

For almost ten years after the Battle of Chaldiran, rival Qizilbash factions fought for control of the kingdom. In 1524, 10-year-old Shah Tahmasp I, the governor of Herat, succeeded his father Ismail. He was the ward of the powerful Qizilbash amir Ali Beg Rūmlū (titled “Div Soltān”) who was the de facto ruler of the Safavid kingdom. However, Tahmasp managed to reassert his authority over the state and over the Qizilbash.

During the reign of Shah Tahmasp, the Qizilbash fought a series of wars on two fronts and – with the poor resources available to them – successfully defended their kingdom against the Uzbeks in the east, and against the arch-rivals of the Safavids – the Ottomans – in the west. With the Peace of Amasya (1555), peace between Safavids and Ottomans remained for the rest of Tahmasp’s reign. During Tahmasp’ reign, he carried out multiple invasions in the Caucasus which had been incorporated in the Safavid empire since Shah Ismail I and for many centuries afterward, and started with the trend of deporting and moving hundreds of thousands of Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians to Iran’s heartlands. Initially only solely put in the royal harems, royal guards, and several other specific posts of the Empire, Tahmasp believed he could eventually reduce the power of the Qizilbash, by creating and fully integrating a new layer in Iranian society with these Caucasian elements and who would question the power and hegemony of the tribal Qizilbash. This included the formation of a military slave system, similar to that of the neighboring Ottoman Empire – the janissaries. Tahmasp’s successors, and most importantly Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629), would significantly expand this policy when during the reign of Abbas I alone some 200,000 Georgians, 300,000 Armenians and many tens of thousands of Circassians were relocated to Iran’s heartlands. By this creation of a so-called “third layer” or “third force” in Iranian society composed of ethnic Caucasians, and the complete systematic disorganisation of the Qizilbash by his personal orders, Abbas I eventually fully succeeded in replacing the power of the Qizilbash, with that of the Caucasian ghulams. These new Caucasian elements (the so-called ghilman / غِلْمَان / “servants”), almost always after conversion to Shi’ism depending on given function would be, unlike the Qizilbash, fully loyal only to the Shah. This system of mass usage of Caucasian subjects continued to exist until the fall of the Qajar Dynasty.

The inter-tribal rivalry of the Turcomans, the attempt of Persian nobles to end the Turcoman dominance, and constant succession conflicts went on for another 10 years after Tahmasp’s death. This heavily weakened the Safavid state and made the kingdom vulnerable to external enemies: the Ottomans attacked in the west, whereas the Uzbeks attacked the east.

Daud Khan Undiladze, Safavid ghulam, military commander, and the governor of Karabakh and Ganja between 1627 and 1633.

In 1588, Shah Abbas I came to power. He appointed the Governor of Herat and his former guardian and tutor, Alī Quli Khān Shāmlū (also known as Hājī Alī Qizilbāsh Mazandarānī) the chief of all the armed forces. Later on, events of the past, including the role of the Turcomans in the succession struggles after the death of his father, and the counterbalancing influence of traditional Ithnāʻashari Shia Sayeds, made him determined to end the dominance of the untrustworthy Turcoman chiefs in Persia which Tahmasp had already started decades before him. In order to weaken the Turcomans – the important militant elite of the Safavid kingdom – Shah Abbas further raised a standing army, personal guard, Queen-Mothers, Harems and full civil administration from the ranks of these ghilman who were usually ethnic Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians, both men and women, whom he and his predecessors had taken captive en masse during their wars in the Caucasus, and would systematically replace the Qizilbash from their functions with converted Circassians and Georgians. The new army and civil administration would be fully loyal to the king personally and not to the clan-chiefs anymore.

The reorganisation of the army also ended the independent rule of Turcoman chiefs in the Safavid provinces, and instead centralized the administration of those provinces.

Ghulams were appointed to high positions within the royal household, and by the end of Shah Abbas’ reign, one-fifth of the high-ranking amirs were ghulams. By 1598 already an ethnic Georgian from Safavid-ruled Georgia, well known by his adopted Muslim name after conversion, Allahverdi Khan, had risen to the position of commander-in-chief of all Safavid armed forces. and by that became one of the most powerful men in the empire. The offices of wakil and amir al-umarā fell in disuse and were replaced by the office of a Sipahsālār (Persian: سپهسالار, master of the army), commander-in-chief of all armed forces – Turcoman and Non-Turcoman – and usually held by a Persian (Tādjik) noble.

The Turcoman Qizilbash nevertheless remained an important part of the Safavid executive apparatus, even though ethnic Caucasians came to largely replace them. For example, even in the 1690s, when ethnic Georgians formed the mainstay of the Safavid military, the Qizilbash still played a significant role in the army. The Afshār and Qājār rulers of Persia who succeeded the Safavids, stemmed from a Qizilbash background. Many other Qizilbash – Turcoman and Non-Turcoman – were settled in far eastern cities such as Kabul and Kandahar during the conquests of Nader Shah, and remained there as consultants to the new Afghan crown after the Shah’s death. Others joined the Mughal emperors of India and became one of the most influential groups of the Mughal court until the British conquest of India.

Legacy

Afghanistan

Qizilbash in Afghanistan primarily live in urban areas, such as Kabul, Kandahar or Herat. Some of them are descendants of the troops left behind by Nadir Shah. Others however were brought to the country during the Durrani rule, Zaman Shah Durrani had a cavalry of over 100.000 men, consisting mostly of Qizilbash Afghanistan’s Qizilbash held important posts in government offices in the past, and today engage in trade or are craftsmen. Since the creation of Afghanistan, they constitute an important and politically influential element of society. Estimates of their population vary from 30,000 to 200,000. They are currently Persian-speaking Shi’i Muslims.